By Jim Hightower

(This feature first appeared on Truthout.org)

Being at the bottom of the heap in terms of social justice confirms the reality of both economic and political inequality that the Occupy movement is protesting.

Being at the bottom of the heap in terms of social justice confirms the reality of both economic and political inequality that the Occupy movement is protesting.

“USA: We’re No. 1!”

Oh, wait — Iceland is No. 1. But we did beat out Poland and Slovakia, right? Uh . . . no. But go on down the rankings and there we are! No. 27, fifth from the bottom. So our new national chant is, “USA: At Least We’re Not Last!”

A foundation in Germany has analyzed the social justice records of all 31 members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), ranking each nation in such categories as health care, income inequality, pre-school education, and child poverty. The overall performance by the United States — which boasts of being an egalitarian society — outranks only Greece,

» Read more about: Social Justice Rankings: America 27th Out of 31 »

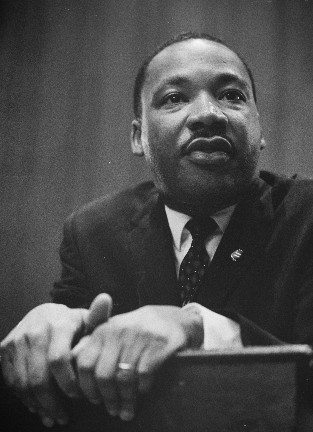

“There are forty million poor people here. And one day we must ask the question, Why are there forty million poor people in America? And when you begin to ask that question, you are raising questions about the economic system, about a broader distribution of wealth. When you ask that question, you begin to question the capitalistic economy. And I’m simply saying that more and more, we’ve got to begin to ask questions about the whole society.

We are called upon to help the discouraged beggars in life’s marketplace. But one day we must come to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring. It means that questions must be raised. You see, my friends, when you deal with this, you begin to ask the question, Who owns the oil? You begin to ask the question, Who owns the iron ore? You begin to ask the question, Why is it that people have to pay water bills in a world that is two-thirds water?

» Read more about: MLK: "These are questions that must be asked." »

In recent weeks the more poetically inclined of us at Frying Pan News have borrowed inspirations ranging from Doctor Seuss to Clement Clarke Moore to express their hopes for the environment and the economy. Now, Jessica Goodheart and Trebor Healey borrow a leaf from Bashō and squeeze green sentiments into a trio of haiku.

(Photo credits: Port of L.A., Brian Ferguson, Louise Rosskam)

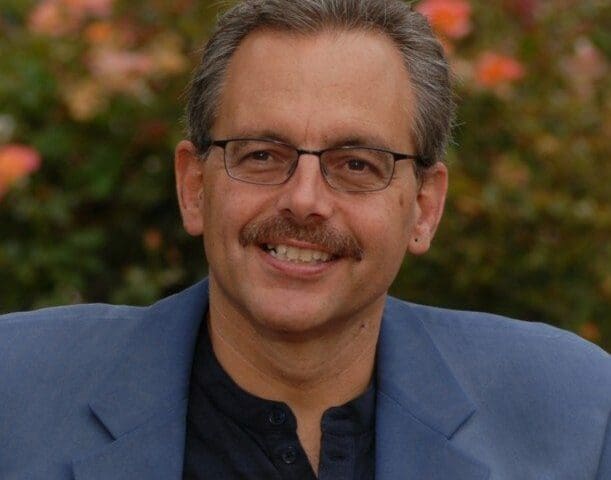

For 25 years, Manuel Pastor has been writing and teaching with keen insight about the economy and how it shapes our lives. Trained as an economist, Professor Pastor serves as the director of USC‘s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity and co-director of the university’s Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration. In recent years, his research has focused on the economic, environmental and social conditions facing low-income urban communities in the U.S. His writing has appeared in dozens of academic and popular publications, and he is the recipient of grants from the Rockefeller, Ford and National Science foundations, among others.

This is the first installment of an ongoing conversation with Professor Pastor about our economy, our politics and the future of Los Angeles.

Frying Pan News: One of the hottest issues this week in L.A.

» Read more about: The Economic Café: A Talk With USC's Manuel Pastor »

I spent last Saturday morning at the five-acre Annenberg Community Beach House complex which, as far as I know, is the only publicly accessible beach facility on the entire coast of our great state. About 200 of us were gathered to honor the 31-year tenure of Barbara Stinchfield, a Santa Monica city staffer who led the effort to finance, design, build and manage the newly opened beach facility for community use.

With a public pool, playground, shaded seating areas, outdoor fountain, public meeting rooms and an indoor-outdoor reception room, the complex, located on the “Gold Coast” adjacent to high-end beach homes, offers ordinary people the beauty of the California beachfront in a tastefully designed building – just what the wealthy can afford to buy in a private beach club.

The “private sector” would have had no incentive to build a public facility like this since it generates no profit and its primary mission is service to the public.

» Read more about: Public Lives: In Praise of a Community Oasis »

The morning after covering the New Hampshire primary, American Prospect and Washington Post commentator Harold Meyerson was getting over a bad cold, but answered a few questions about whether the conservative electorate was becoming more sympathetic to populist pitches.

Frying Pan News: All of a sudden pro-business presidential candidates have been backpedaling or “clarifying” the red-meat comments that they’ve been throwing to their base – comments deriding Americans who are too lazy to be millionaires, or celebrating the joy of firing people. Are candidates suddenly feeling the average person’s pain?

Harold Meyerson: I think Mitt Romney crossed the line when he said he likes firing people. When Romney says it his background as a venture capitalist comes into play. As an actor he’s precisely the guy central casting would send to play a Wall Street executive.

FPN: So you don’t think the Republican candidates will be playing the populist card?

On February 1, 2012, I will be out of a job. That’s because at 12:01 a.m., more than 400 California redevelopment agencies will go out of business, including the Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency (LACRA), where I have served as a volunteer (meaning unpaid) commissioner for nine-and-a-half years. California’s $6 billion annual economic development program used by cities to revitalize distressed neighborhoods will disappear.

This is happening because of the legislature’s adoption of Assembly Bill 26X, which was upheld by the California Supreme Court on December 29, 2011. While the consequences for me are different than for the hundreds of LACRA employees who will eventually lose their livelihoods, it’s still a personal blow.

Because, for nine-and-a-half years I have devoted a significant amount of volunteer time to making redevelopment a winning proposition for low-income communities in Los Angeles. While I admit that I have not always been successful,

(Editor’s Note: This post by Zak Rosen first appeared on Yes Magazine.)

For nearly a decade, Gloria Lowe was a final-line inspector for Ford Motor Company, checking new Mustangs as they rolled off an assembly line in Dearborn, Michigan. She worked at the River Rouge Complex, a hulking, mile-long structure that, back in the 1930s, employed as many as 100,000 people. By the time Gloria started working there, just a fraction of the workers remained. (Since the year 2000, metropolitan Detroit has lost about 200,000 manufacturing jobs, despite experiencing a slight gain since 2009.)

Then one day, in 1999, Gloria was on her way back into the plant after parking yet another Mustang when an automated, two-thousand pound metal door came loose and crashed down on her head. She was diagnosed with left-side nerve damage from the top of her brain down through her feet,

» Read more about: Work, Reimagined: Detroit Gets Creative »

Meet Charles Scott Howard, Job Killer. Mr. Howard, 51, seems an unlikely actor to play this dreaded role – he’s been a Kentucky coal miner for three decades. The rough-hewn Howard has earned the lasting hatred of Big Coal by shutting down mining operations whenever he’s felt his workplace was unsafe. And by speaking to government officials and the media, he has become a figure feared by corporate America – a whistleblower.

For years Howard has documented dangerous conditions in mines — usually subterranean hell holes owned by Arch Coal Inc. For calling attention to escapeways flooded with waist-high water, poorly hung ventilation curtains and worn-out mine seals that separate combustible vapors, Howard has lived an almost seasonal employment cycle of being fired, blackballed and then, thanks to his lawyer’s efforts, reinstated.

“Howard’s career,” wrote Dave Jamieson, in an absorbing Huffington Post profile last September, “has coincided with the decline of unions in mining and other American industries,

» Read more about: Big Coal vs. The Miner Who Knew Too Much »

My wife and I are bird nuts. Our weekends are spent hiking around the hills of Los Angeles with binoculars in hand. I have a somewhat louder jaunt and am sometimes given a scowl from Christine if I unintentionally flush a bird from its tree before either of us can get a good look. She’s a much better birder. She’s quiet and aware. She knows the calls, the chirps, trills and quacks.

“Listen to that goldfinch,” I’ll tell her.

“You think that’s a goldfinch?” she’ll smirk. We argue about the call until a scrub jay flutters out of the tree in front of us. As I say, she has a really good ear.

My fascination with birds started with the condor — the largest flying land bird in North America and one of the world’s most highly profiled endangered birds.

In the mid ’80s my Dad’s cattle ranch outside of Glennville,