Last week economist Manuel Pastor and I went to talk to the L.A. Times editorial board about the importance of “updating” its position on living wage policies. The week before, the Times had written an editorial in support of the MTA construction careers policy, but at the same time criticized living wage policies as part of “a long and mostly unsuccessful history of using public resources to try to engineer positive social outcomes.”

Over the years, the L.A. Times editorial board has written at least a dozen editorials criticizing the various living wage policies adopted by the city and county of Los Angeles as job killers, bad economic policy, government interference with the market and many more names.

One of the things that I have written about before is that living wage policies in Los Angeles have actually been very successful.

» Read more about: Getting the Living Wage Message to the LA Times »

Seven a.m. My alarm jolts me out of a deep slumber. I make my way to the bathroom and run a hot shower. Fifteen minutes later I proceed to the kitchen to start my morning coffee, Dunkin’ Donuts coffee, to be exact. I fill my cup and open the fridge to get some milk. No milk! My morning ritual comes to a grinding halt. No relative drank it all and placed the empty container back in the fridge; I’m just incapable of keeping my fridge stocked. I consider running to the supermarket, then realize that the nearest one is a mile away. I grudgingly put on a coat and walk two blocks to the corner store. I walk past the tiny aisle of wilted lettuce and mushy tomatoes to the combination dairy-alcohol case. I groan audibly. The shop only carries gallons of whole milk for almost $5 a gallon. Thank goodness I’m only out of milk.

» Read more about: Hey LA, Where’s the Beef? And the Broccoli? »

Mr. Frank McCourt

Los Angeles Dodgers LLC

1000 Elysian Park Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90012

Dear Frank,

In my 17 years, I’ve been to over 150 Dodger games. I’ve never seen them better than in 2009, when they defended the National League West title and played the Phillies in the NLCS. You were owner then, remember? Remember Mannywood? We swept the Cardinals in the Division Series. So much promise, so much hope.

Of course, it didn’t last. The day before we played the Phillies in Game One, you and Jamie announced you were getting divorced. I never understood how you thought that was a good idea, to announce it that day. We lost to the Phillies in five games.

And the unraveling began. You fired your wife. We found out neither of you paid any income taxes from 2004-2009. You had the Dodger Dream Foundation pay your friend $400,000 in one year.

By Jennifer Medina

(Note: This feature appeared on the New York Times Web site February 1.)

CLAREMONT, Calif. — The dining hall workers had been at Pomona College for years, some even decades. For a few, it was the only job they had held since moving to the United States.

Then late last year, administrators at the college delivered letters to dozens of the longtime employees asking them to show proof of legal residency, saying that an internal review had turned up problems in their files.

Seventeen workers could not produce documents showing that they were legally able to work in the United States. So on Dec. 2, they lost their jobs.

Now, the campus is deep into a consuming debate over what it means to be a college with liberal ideals, with some students, faculty and alumni accusing the administration and the board of directors of betraying the college’s ideals.

We are the 99 percent. Well, yes we are, but not everyone among us thinks so. Lots of people think they are part of the 1 percent when they aren’t even close. According to Harper’s Index 13 percent of Americans think they are part of the1 percent, and 28 percent of “Hispanic Americans” think they are part of the 1 percent. Since these are statistical impossibilities, it makes me wonder why people don’t identify with who they are instead of who they are not.

Some people identify with the rich because they expect to be rich some day. That is why so many low-income people play the lottery. One day their ship will come in. On the other hand, many people think that if they work hard, climb the ladder and make a few clever deals, they too will be rich. Some 43 percent of Americans actually think that.

That was the unlikely message to emerge from a series of town halls that have been held around the city over the last few months hosted by RePower LA, a new citywide coalition. From East and South L.A. to the Valley and the Westside, environmentalists, business owners and young people in need of jobs have sung the praises of energy efficiency.

Why the commotion? It’s over the promise and potential of making the LADWP, the nation’s largest municipally owned utility, a leader in energy efficiency. Energy efficiency programs can keep our bills low, saving businesses and residents hundreds or thousands of dollars a year. They also provide local jobs. And they can help wean us off our reliance on dirty energy sources that pollute our air and threaten our health.

Thousands of Los Angeles residents and businesses want the LADWP to invest in a sustained manner in programs that make our homes and businesses more energy efficient and create good jobs,

» Read more about: LA and Energy Efficiency: Less Is Way More »

Arturo de los Santos, a 46-year-old former Marine who lives in Riverside, California, doesn’t usually listen to National Public Radio, but a friend told him to pay attention to a disturbing report broadcast Monday on NPR’s “Morning Edition.” The report disclosed that Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored mortgage company, whose mission is “to expand opportunities for home-ownership,” invested billions in mortgage securities that profited when homeowners were unable to refinance.

De los Santos is one of those homeowners that Freddie Mac bet against. Sunday night he got a court summons at his door from Freddie Mac stating that the mortgage giant was going to evict him.

But he’s fighting back, pledging to get arrested rather than leave voluntarily if Riverside County sheriff’s deputies try to remove him, his wife and four children from the home they’ve lived in for almost a decade. He is part of a growing movement of Americans inspired by Occupy Wall Street to stop banks and other lenders from foreclosing on their homes.

In the summer of 1963 between high school and college I badly needed a job. A friend from my class at Hollywood High School, who thought of himself as a free thinker and was headed to Reed College, told me his dad had a position open for a secretary and, with his help, I could get hired.

Quality Collection Company was located in a grungy office building in downtown L.A. and was run by my friend’s father and uncle who pretended they were lawyers. The company purchased contracts for items sold door to door in mostly black and Latino neighborhoods in Los Angeles and attempted to collect what was owed on those contracts. Families may have signed up for a deep freezer, not realizing that expensive monthly purchases of meat were part of the deal; or found they had committed to purchasing aluminum siding they didn’t need and couldn’t afford.

My job was to send out the increasingly shrill collection notices on these contracts that included more and more bold black or red lettering and exclamation marks threatening to garnish their wages or repossess their belongings if they didn’t pay up.

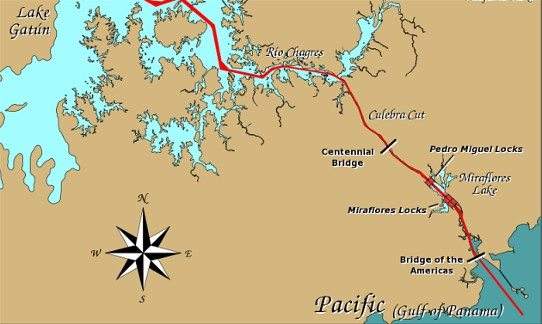

About half of all U.S. container trade comes through West Coast ports. Our most important trade partners, by far, are the Asian nations. (China and Japan alone account for over half of all the stuff we import.) The West Coast ports handle the bulk of this trans-Pacific trade. And the neighboring Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach claim the lion’s share of all of this: About 40 percent of Asian imports come into the U.S. through the San Pedro Bay ports. In Southern California, we arguably sit at the single most important locus of global commerce.

And trade has largely done well for us. It is a major driver of our regional economy, swapping places every couple years with tourism as the biggest job creator. The ports generate tens of thousands of very good jobs, mainly for longshoremen. (The ports also generate many thousands of crappy jobs for truck drivers and warehouse workers,

» Read more about: The Panama Canal: Big Business’ Big Stick »

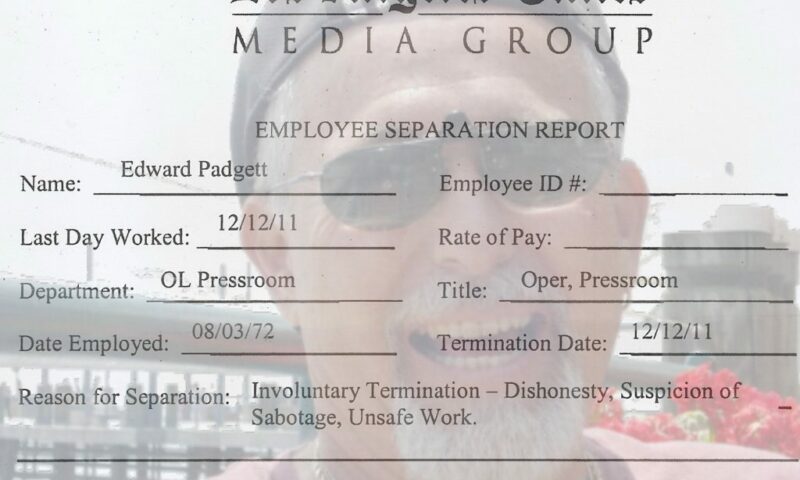

Ed Padgett was driving in the rain to a union meeting when the L.A. Times called to tell him he was fired. The pressman, a third-generation Times employee, listened in shock last December to an HR woman’s voice explain he was being dismissed for “safety violations, dishonesty and suspicion of sabotage.”

That last charge had a bittersweet irony. Padgett had been at the paper for more than 39 years and had done everything he could to help it prosper – even as members of the corporate wrecking crew that drove the paper into bankruptcy were still counting their money.

“It was similar to jumping into an icy cold pool of water,” Padgett recalls. “I felt like crying because I’d been there so damn long, but I soon got over it.” He drove on to his meeting in La Mirada, but hasn’t been back to the Times printing plant on Olympic Boulevard to clean out his locker.

» Read more about: LA Times: Layoffs, Sabotage and Suicides? »