Powerful lobbyists represent both oil and gas interests and environmental groups.

Two blocked climate bills show the oil and gas industry, related unions can still sway the new Democratic House majority.

Legislation aims to shine a light on corporate climate pollution and carbon offsets.

Former officials push strategies on behalf of fossil fuel clients, threatening climate and communities, say critics.

Lax reporting laws leave politicians and the public in the dark about legislation backers.

Santa Fe’s easy familiarity with energy industry representatives illustrates how one of the most powerful lobbies is treated within state government.

Co-Published by Fast Company

How much influence has a former Jerry Brown staffer-turned-lobbyist had over the governor?

Climate-change activists hoping to hear the governor propose a new climate initiative during his State of the State speech Thursday were disappointed.

On the list of society’s most reviled professions, somewhere between tax collector and a member of Congress, sits the lobbyist.

The nurses who showed up at state Senator Richard Pan’s Capitol office in May were furious. They had been assured by Pan, a Democrat from Sacramento, that he would be on their side when it came time to vote on Senate Bill 346, a charity care measure aimed at providing transparency to the state’s currently murky rules governing tax-exempt status for nonprofit hospitals.

But Pan, a physician who has risen to prominence this year as the sponsor of a mandatory school vaccination bill, abstained when the bill came up for a vote in the Senate’s health committee, effectively killing it when it fell one vote short of passing in that committee on April 29. The nurses alleged that the bill died because Pan withdrew his promised support after heavy, last-minute lobbying by the California Hospital Association (CHA). Pan’s spokesperson, Shannan Martinez, later issued a denial,

» Read more about: The Persuaders: California Hospital Association »

Here’s something you probably didn’t know happened in California in the last few years, and maybe it’s something you never imagined could happen: In 2011, two high-ranking state regulators were fired from their posts for pissing off the oil industry. No one really disputes the veracity of that statement; not even Governor Jerry Brown. “They were blocking oil exploration in Kern County,” the Sacramento Bee reported Brown announcing at an event six months later. “I fired them, and oil permits for drilling went up 18 percent.”

Catherine Reheis-Boyd, president of the Western States Petroleum Association, also celebrated without restraint, unconcerned that the people of California might detect her hand guiding the Governor’s pink-slip pen. After the firings, Reheis-Boyd boasted to the Los Angeles Times that her industry once again had a “clear pathway for people to get permits and proceed with drilling in this state.

» Read more about: The Persuaders: Western States Petroleum Association »

“Something always seems to be starting in California,” Angelo Amador, an attorney and vice president for the National Restaurant Association, told Bloomberg News.

It was 2012 and his remark was prompted by a California state Supreme Court decision favoring an employee’s right to have defined meal-break times. The association—dubbed “the other NRA” for its lobbying muscle, with annual revenues of $71 million in 2013–had vigorously opposed policy that required employers to ensure that workers take rest and meal breaks rather than leaving it to the employees to push back against managers to enforce break provisions.

Amador’s NRA is perhaps the largest trade group that you have never heard of, and supports an “institute” run by a PR firm that churns out opinions and papers to shape policy debates.[divider]

Also read these stories in our “Persuaders”

» Read more about: The Persuaders: California Restaurant Association »

Ever wonder how a bill doesn’t become a law?

One week we’ll be hearing all about a proposed law intended to improve the quality of life for the majority of Californians, a bill that seemingly has on board every state Senator or Assembly member who cares about the environment, consumer rights or worker safety. Then, suddenly – Poof! – the next thing we know, the legislation has been killed in committee or withdrawn by its sponsor.

Whenever we hear of these kinds of Sacramento stories, we might assume it’s the work of the Chamber of Commerce. After all, the CalChamber is the state’s big guard dog defending corporate interests by placing long-overdue bills on its dreaded Job Killer list. But the Chamber isn’t the only bully on the block – it often has help from a gang of powerful lobbying organizations that represent the individual interests of very specific industries.

» Read more about: Today: “The Persuaders” Looks at Corporate Lobbying »

Seventy-three percent of polled Americans believe that corruption in government is widespread. That’s a lot of distrust. And it leads to a lot of cynicism. A big chunk of that corruption comes from the revolving door of politics, greased by money so great it would make most of us faint-of-heart.

Pols move from elected office to big offices on Wall Street or to lobby firms in state capitals across the nation. Government regulators have often left the very industry they are charged with regulating to join a commission in the sector they are supposed to regulate. Later, they return to the same business they once worked for.

Of course these people are not making decisions in the best interest of the consumer, since even when they are on the government payroll they carry the acute awareness of soon returning to that corporate office. They want to regulate without annoying too many future employers.

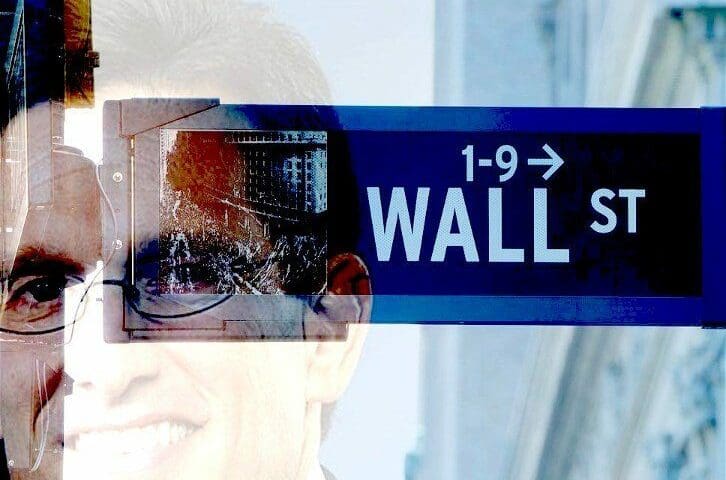

When House Majority Leader Eric Cantor lost his primary bid for re-election, he wasted no time cashing in on new opportunities. He didn’t even wait for his term to end before resigning his office August 18 – leaving his constituents unrepresented for three months, and making the leap to big bucks on Wall Street. His base pay in his new position with the investment firm Moelis & Co. is $400,000 for the remainder of the year, plus a $400,000 signing bonus. He also gets a million dollars-worth of restricted stock – altogether about 26 times the average income of Virginians in his old district.

What makes an ex-Congressman so valuable to an investment firm based in New York City? To be clear, he cannot return to the floor of the House to lobby his former colleagues on a bill. Congress ended that practice in the middle of the last decade.

» Read more about: The Big Money: Eric Cantor Goes to Wall Street »