A year and a half ago, I wrote an article for the Huffington Post that I called “Will the Killing of Trayvon Martin Catalyze a Movement Like Emmett Till Did?” I pointed out that Rosa Parks was thinking about Emmett Till — a 14-year-old African American who was brutally murdered by two white thugs in Mississippi in August 1955 — when she refused to move to the back of the bus in December of that year and sparked the Montgomery bus boycott which, in turn, triggered the civil rights movement.

At the time, I hoped the answer to my question would be yes, but I wasn’t sure. I wondered whether the protests over the murder of Trayvon Martin, and the acquittal of his killer George Zimmerman, would coalesce into a sustained movement.

Now we can see that, indeed, a movement for social and racial justice has emerged from the Trayvon Martin murder and more recent events —

» Read more about: The Dawn of a New Racial Justice Movement »

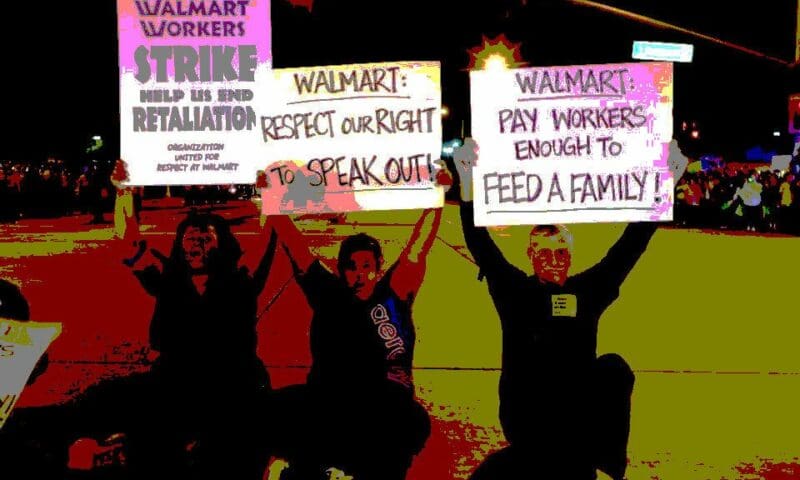

Earlier this month two dozen workers, clergy and other community folks sat down in the aisles of the Walmart store in Pico Riviera, then moved into the streets, where they were promptly arrested. Why would any group of people – much less some not even directly involved in working at Walmart– voluntarily put themselves in a situation they know will lead to their arrest? Because they feel the injustice of minimum wage jobs, whose schedules are unpredictable and deliberately fall just short of offering enough hours to provide health care benefits and paid sick days. These are among other practices that stores like Walmart refuse to rectify.

Without other ways to redress these grievances, people undertake nonviolent civil disobedience. They decide to deliberately break some small law rather than ignore a larger injustice, as Martin Luther King Jr. argued for during the civil rights movement. They break the law, but they are not criminals,

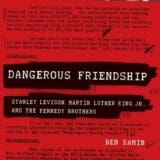

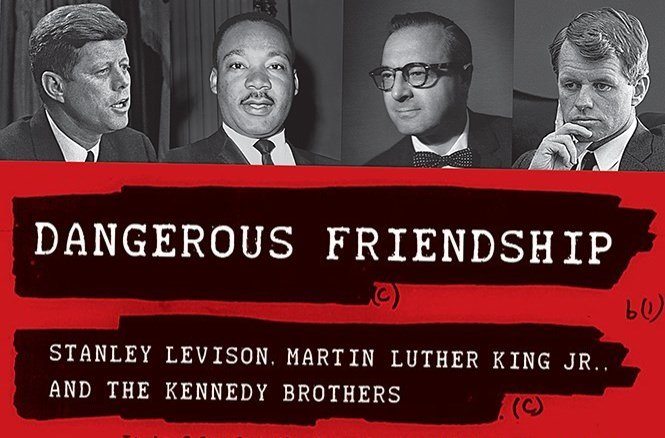

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover tried to erase the name of Stanley Levison from civil rights history in the 1960s. Now historian Ben Kamin is putting Levison firmly back into the historic record with his new book, Dangerous Friendship: Stanley Levison, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Kennedy Brothers.

Levison was a successful Jewish businessman and member of the American Communist Party until 1956, when the Soviet invasion of Hungary left him disillusioned. He refocused his organizing skills, business and labor contacts, energy and intelligence to support the work of Martin Luther King Jr., helping to found, manage and fund King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In the process, Levison became an intimate friend of King and part of the tight circle of confidants who helped develop King’s campaigns and sustain him emotionally.

What drew Levison, and hundreds of other American Jews like me,

» Read more about: Book Review: MLK’s Dangerous Friendship »

“I question America ” — the famous words spoken by civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer 50 years ago this week at the tumultuous Democratic Party convention in Atlantic City — is a fitting reflection of the soul-searching that the country is once again going through in the wake of the turmoil in Ferguson, Missouri.

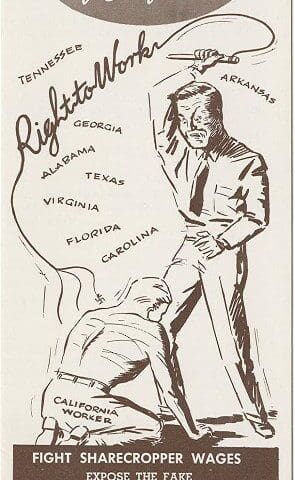

To understand both the progress America has made, and the many challenges it now faces, in terms of racial justice, it is useful to remind ourselves of the battle that occurred a half century ago and the life of Ms. Hamer, a sharecropper and activist from the Mississippi Delta who galvanized the country with her stirring words and her remarkable courage.

In her testimony before the credentials committee at the Democratic Party’s convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Hamer explained why the committee should recognize the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party over the state’s segregated official party delegation.

Most students of the 1960s may know about the FBI’s obsessive surveillance of Martin Luther King Jr. and how the bureau’s shadowing and bugging of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s president would lead federal agents to infiltrate the civil rights and peace movements. Now, a new book by Ben Kamin throws a spotlight on the man whose close friendship and collaboration with King provoked J. Edgar Hoover’s wrath and paranoia. Dangerous Friendship analyzes the relationship between King and Stanley Levison, a lawyer and wealthy businessman with a radical past. The book tells how Levison, known as King’s ghostwriter and closest white friend, advised King on strategy and raised righteous amounts of money for his cause; the story also shows how their friendship prompted the Kennedy White House to force King to shun Levison for more than a year.

Kamin, a nationally known rabbi, also explores how Levison’s personal solidarity with African American struggles reflected a traditional Jewish embrace of equality and social activism.

» Read more about: Tonight: Ben Kamin on MLK’s “Dangerous Friendship” »

Last month Julian Bond, the pioneering civil rights activist and former Georgia state legislator, addressed an audience gathered in Jackson, Mississippi, to celebrate and analyze the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964. Bond’s speech appears for the first time here, with his permission. [divider]

In 1961, when Martin Luther King Jr. addressed the Fourth Constitutional Convention of the AFL-CIO, he spoke of the “unity of purpose” between the labor movement and the movement for civil rights. He said:

[tabs type=[tab_title][tab]“Our needs are identical with labor’s needs: decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community. That is why Negroes support labor’s demands and fight laws which curb labor. That is why the labor-hater and labor-baiter is virtually always a twin-headed creature spewing anti-Negro epithets from one mouth and anti-labor propaganda from the other mouth.

» Read more about: Exclusive: Julian Bond on Labor and Civil Rights »

“When you’re in Mississippi the rest of America doesn’t seem real. And when you’re in the rest of America, Mississippi doesn’t seem real. ”

— Bob Moses, Mississippi Freedom Summer Director

The Mississippi Freedom Summer project of 1964 was born of necessity. The ranks of civil rights workers in the state were being devastated and the nation needed to pay attention. The proposal to bring hundreds of college students into Mississippi for the summer to work as voter registration and Freedom School volunteers was controversial. Opponents worried that the mostly white students didn’t know the state, might distract from building grassroots leadership and could provoke even more retaliation from Mississippi segregationists. But according to civil rights veterans who convened the 50th Anniversary gathering of Mississippi Freedom Summer in Jackson this past June, it was the local leaders, like former sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer, who strongly supported the idea.

Social justice activists often think that when things are terrible, people will rise up and protest those conditions until they see significant change, and sometimes they do. But usually, especially in recent decades in this country, they don’t. My friends, as well as other readers of the Frying Pan, often ask, Why not?

I always return to one of the classic analyses of dramatic social change, Crane Brinton’s Anatomy of Revolution. The book follows the trajectory of four historic revolutions: England, France, America and Russia. In each, he argues, regime change did not happen because conditions were at their worst. Instead they occurred when the circumstances of everyday life were actually getting better but did not match the hopes of people. Revolution happened, Brinton says, in the widening gap between expectation and reality.

That explanation probably clarifies why demonstrations in Greece and Spain have met with frustration,

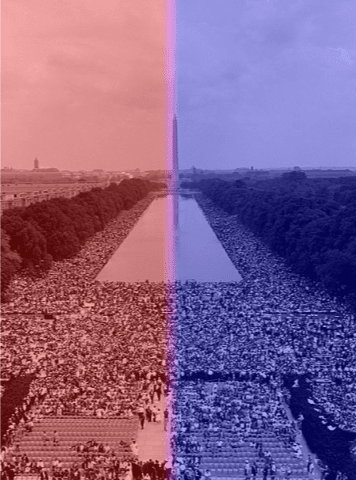

Fifty years ago, just a year out of high school, I sat in my parents’ small living room engrossed by images on the flickering black and white TV screen. Something called the March on Washington was running live — the whole event, as I recall, which network television did in those days. I’m not sure why I was not at work or why I was alone in the house, but I remember that tears came to my eyes, just as they do now as I think back on that day.

My parents were originally from the South, but both grew up in Southern California. My mother had been born in Mississippi, moved to Texas and then Inglewood. My father came from Texas to La Crescenta. After they married and my father became a minister, Northern California was home, but the ethos of white superiority and other ethnic and class inferiorities were engrained.

What would the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. march for if he were alive today?

America has made progress on many fronts in the half-century since King electrified a crowd of 200,000 people, and millions of Americans watching on television, with his “I Have a Dream” address at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. But there is still much to do to achieve his vision of equality.

Fortunately, many Americans are involved in grass-roots movements that follow in his footsteps. King began his activism as a crusader against racial segregation, but he soon recognized that his battle was part of a much broader fight for a more humane society. Today, at age 84, King would no doubt still be on the front lines, lending his voice and his energy to major battles for justice.

Voting rights: Along with other civil rights leaders, King fought hard to dismantle Jim Crow laws that kept blacks from voting.

» Read more about: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Spirit Is Still Marching »

August 28 of this year marks the 50th anniversary of the famous March on Washington. For many people, the march was simply the site where Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. However, the full name of the march was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and it marked a high point of the modern Civil Rights Movement, after black communities and their supporters throughout the country boycotted buses, sat-in at lunch counters, rode in Freedom Rides, and marched in the streets. These massive protests were aimed at destroying, once and for all, the era of legal segregation — which had been a blot on this country since the end of slavery.

But organizers knew that the end of segregation without good jobs was no freedom at all. So, four of the march’s ten demands focused on employment issues. (See the ten demands and other items in the march’s “Organizing Manual No.

As we settle further into Black History Month, it’s the perfect time to reflect on Martin Luther King Jr. and his often under-acknowledged passion for economic justice. King stands as a pillar of civil rights leadership and the movement for equal rights. His legacy is special to the black community, and as a symbol, he has become an extraordinary role model to all people. However, to see King’s legacy only through this lens would miss much of his work. King was also a union ally and champion of economic justice.

King understood clearly that the battle for racial equality would be empty without a parallel fight for economic equality. “[What] will [the Negro] gain by being permitted to move an integrated neighborhood if he cannot afford to do so because he is unemployed or has a low-paying job with no future?”[i] Having equal rights without the means to exercise those rights becomes an empty promise,

In an action that already feels like ancient history, Congress voted earlier this month to avoid the “fiscal cliff.” While much remains to be settled, the revenue side of the issue got resolved because 84 House Republicans joined 172 Democrats to support the solution negotiated between the President and the Senate. In some ways, such bipartisanship was a moment of déjà vu from a time, nearly 50 years ago, when two pivotal civil rights bills were being considered. Then, Lyndon Johnson was President and both houses of Congress were in the hands of Democrats. Martin Luther King was in the streets. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was registering voters. The 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act were passed by Republicans joining Democrats to move the President’s legislation into law.

In both circumstances – today, as then – it was one party’s Southern flank that refused to go along with its leadership.

» Read more about: Great Migrations: Our Civil Rights Laws and Their Legacy »