Figures compiled from campaign contribution records show that fossil fuel industries donate almost exclusively to Republican candidates. “They’ve gone out of their way to help oil and gas and coal,” says one environmentalist.

Both ozone and particulate pollution are attributed to oil and gas production, agribusiness, mega-dairies, power generation, heavy equipment and truck traffic – many of the Central Valley’s major businesses.

Activists have sent a loud and clear message to the California Public Utilities Commission: L.A. and the state should make electric transportation in the city and at the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports a priority.

The Southern California Association of Governments’ “100 Hours” initiative is intended to solve L.A.’s traffic woes, and is named for the average number of hours Los Angeles drivers spend in traffic jams every year.

Some environmental activists worry that proposals floated by Governor Jerry Brown and legislative leaders to extend cap-and-trade, the state’s primary tool in its climate fight, will bar local air districts from regulating carbon dioxide emissions at state-regulated facilities.

Co-published by Fast Company

Is California’s strict zero-emissions strategy, which forces car makers to market exhaust-free hydrogen-fueled and battery-powered vehicles, really the most consumer friendly, egalitarian way to go?

Dean Kuipers on why Sacramento punted on Cap-and-Trade.

(The following talk was given last night by Robert Gottlieb at Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design.)[divider]

This is an interesting venue for my talk. If, historically, the school has been engaged in making the automobile a more attractive object for consumers and industry alike, then my talk seeks to do the opposite. Can we envision eliminating or at least reducing the automobile’s role in Los Angeles? And, if so, what would that mean for the ArtCenter College of Design and its long history with the automobile?

Let me start with a recent New York Times Sunday Business article on the design firm Ideo with its slogans of “slow becomes fast” “auotomobility” and “autonomous driving.” The headline for the piece was “Helping Ford Go Beyond the Car,” although it could have also been headlined “How to save the car while also capturing its alternatives.” Is this the route for the ArtCenter College of Design?

» Read more about: Imagining a Los Angeles With Fewer Cars »

Four years ago, Robin Kutchai lost her husband to cancer. “We got the diagnosis that his body was full of tumors two weeks before he died,” she said, perched at the bar of the Woodland Hills Hilton, where she’s temporarily holed up. They had been married 10 weeks after they’d met, 35 years ago. Telling the story, her large, neatly made-up eyes welled with tears.

After her husband’s death, Kutchai sold their Simi Valley house and bought a townhouse in Porter Ranch, where she found a sense of belonging to help her through her grief. “It was always such a wonderful area,” she said. “It was a place where I felt safe being alone.”

The AQMD insisted it lacked the authority to order the draining of the Aliso Canyon well.

That all changed dramatically this past autumn, when the air in the far northwestern San Fernando Valley community became saturated with the rotten-egg smell associated with natural gas — a consequence of a chemical added to the odorless gas to make it detectable.

» Read more about: Porter Ranch: Nosebleeds and Dead Hummingbirds »

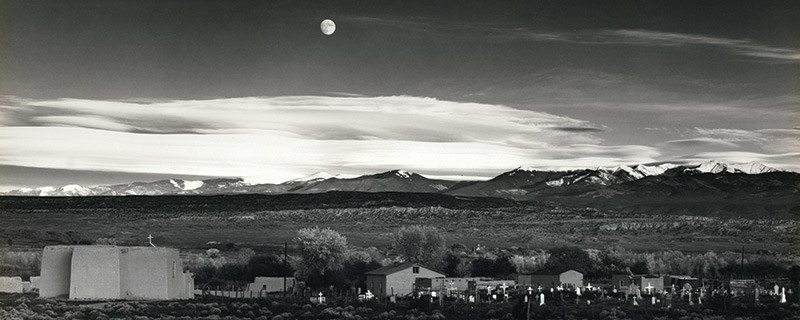

The rural Southwest feels vast and empty. Driving from Los Angeles to New Mexico, my wife Susan and I saw sweeping landscapes of alluvial fans and sheer cliffs, and mesas that stretched as far as we could see. Just the idea that people carved out a way of life on these lands left us in awe of our ancestors and, before them — centuries before them, millennia even — the first people who lived here.

People still live on this arid earthscape. They populate the small towns along the railroad tracks. They dwell in pueblos at the tops of mesas. They survive tucked into corners of cliff sides and in the bottomlands of rivers. Driving through such rugged beauty made us aware of the power of nature and the relative powerlessness of human beings in that kind of environment.

“Wild” no longer exists, even in the vast expanses of the Southwest. » Read more about: A Cease-Fire With Nature? »

A common refrain among opponents of clean air, water and endangered species is that environmental regulation kills jobs. From some perspectives, they’re occasionally right: Go talk to a coal miner in Kentucky staring down the Obama administration’s new rules for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from new power plants, or an Oregon tree-feller on the topic of spotted owls. When rules to protect nature and public health kick in, whole economies sometimes die.

But it’s also true that people living in poverty suffer disproportionately from industrial pollution, and that wealth benefits from the long-term protection of resources — without restraint, after all, one day there’d be no forests to log. So a United Nations’ Brundtland Commission in 1987 proposed another way of looking at the situation, one that wouldn’t pit laudable values against each other, but would instead regard economic and environmental health as inseparable. The Brundtland participants coined the term “sustainable development” and,

» Read more about: Jobs & the Environment: An L.A. County Report Card »

One day late last year, retired police officer Robert Mitchell took several visitors on a tour of the West Fresno community where he has lived for decades. But it was hardly a nostalgia excursion.

This is an encore posting from our State of Inequality series

First, there was a stop at Hyde Park, a former dump. There was another at a sports complex and fishing pond built on a Superfund cleanup site. And still another at a controversial meat-rendering plant operated by Darling Ingredients Inc. that residents say has spewed foul smells into nearby residential areas for more than half a century.

“You constantly had the horrific odor of the processing that occurs here at Darling,” said Mitchell, a thoughtful man with a bushy white beard and deep voice. He and his visitors stood outside the Darling plant,

» Read more about: Hell’s ZIP Code: Clearing the Air in West Fresno »