Photojournalist Ted Soqui shot these images for today’s story by Sasha Abramsky, Renting in Los Angeles — Dislocation, Dislocation, Dislocation.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

California’s housing crisis is a complex one, as befits a state with a population of close to 40 million people, spread out over 163,696 square miles, and with some of the country’s largest cities and fastest growing population hubs, as well as some of its most rugged rural areas.

See More Stories in Capital & Main’s Affordable Housing Series

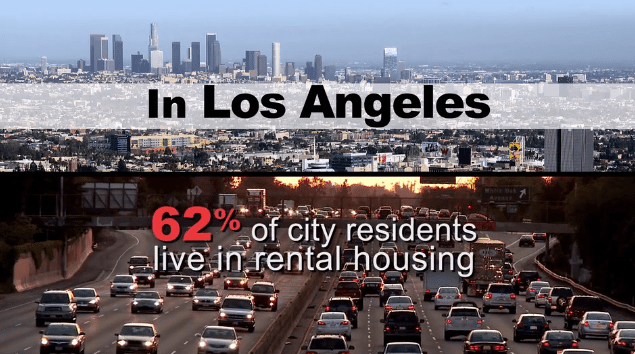

Los Angeles’ Skid Row sprawls just a few blocks from the skyscrapers of downtown and showcases one of the developed world’s largest concentrations of long-term homeless people. They live in tents and jerry-rigged shanties along the sidewalks and in vacant lots, surround social service agency buildings and provide a vista of misery stunning in its intensity. Only a few miles away, middle- and working-class tenants are being driven from their rent-controlled homes into the exurbs or onto friends’ and relatives’ couches. The causes of this diaspora are developers seeking to capitalize on Hollywood’s soaring real estate values and the city’s “densification” development strategy that prioritizes large-scale,

» Read more about: Affordable Housing: Introduction to a Crisis »

“No Direction Home” reaches many troubling conclusions about California’s housing market

With the lead poisoning tragedy in Flint, Michigan still playing out in the national headlines, we’ve been due for good news about our nation’s water—and Wisconsin just delivered it.

With the lead poisoning tragedy in Flint, Michigan still playing out in the national headlines, we’ve been due for good news about our nation’s water—and Wisconsin just delivered it.

Yesterday, state leaders scrapped a bill that would have made it easier for private corporations to buy municipal water and sewer utilities across the state. The bill, introduced at the request of a for-profit water company based in Pennsylvania, would have made it more difficult for Wisconsin residents to vote on who controls their water.

The evidence against privatization is plain as day. Customers of Wisconsin’s only privately owned system—which services the city of Superior—pay the highest rates in the state. On top of the costs of water and infrastructure maintenance, Superior’s residents pay an additional nine percent to cover their private operator’s profit margin and higher private-sector debt costs.

And Superior isn’t an outlier.

» Read more about: Wisconsin Dodges Water-Privatization Scheme »

What can happen when voters use electoral politics to raise the minimum wage? For one thing, some mainstream media can go on the attack by editorializing in coverage that poses as “news.”

Take, for example, ABC Channel 10’s recent television coverage of business’ fight to strangle Sacramento’s $15-an-hour minimum-wage measure in the petition process. Region Restaurants, a trade group of caterers and eateries, is rallying public opinion against the capital city’s minimum-wage measure that could, with 21,503 registered voter signatures, qualify for the November 2016 ballot. The current California minimum wage is $10 an hour.

Anchorman to Minimum Wage Petitioners: “Be careful of the unintended consequences.”

In a February 10 broadcast of the station’s “Real Money” news segment, co-anchor Dale Schornack announced the $15 measure would begin in 2017. His statement was off by three years – close enough for a game of horseshoes,

» Read more about: Sacramento Waiters Make $50 an Hour, TV Station Claims »

Even as Saturday’s death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia was setting the stage for what promises to be an incendiary battle of wills between Republican leaders in Congress and President Obama over naming a replacement for a man considered a cornerstone of the court’s conservative majority, California teachers and public-sector unions across the country were breathing a sigh of relief.

That’s because the 79-year-old Scalia, who died in his sleep on Saturday at a remote resort in West Texas, appeared to hint during last month’s oral arguments that he would vote along ideological lines with his fellow conservative justices in affirming the plaintiffs’ side in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, in what most court observers were anticipating to be a 5-4 vote. That case, whose decision was expected by the end of June, seemed all but guaranteed to overturn the High Court’s 1977 Abood v.

» Read more about: Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia Dies and Labor Gets a Stay »

Many charter school advocates — often guided by a “free market” ideology — claim that charter schools force traditional public schools to innovate and provide better education. But in Detroit, where teachers and parents this week performed “walk ins” to show support for the city’s ailing public schools, the exact opposite has been true.

Detroit’s schools are in rough shape. The city’s traditional public school district, Detroit Public Schools (DPS), could face bankruptcy by April. On a recent tour of DPS schools, Mayor Mike Duggan found crumbling facilities, dead rodents, and children wearing coats in freezing classrooms.

But even though Detroit’s residents elected him, Duggan can’t do much to help. DPS has been under state control for seven years, ruled by a series of “emergency managers” with unchecked authority over democratically elected local officials. The same tactic of “running government like a business” played a crucial role in the Flint water crisis.

» Read more about: Running Schools Like Businesses — Into the Ground »

It’s not news that it is tougher to buy a home in the U.S. than it was 40 years ago. But what may come as a surprise to the roughly 7. 7 million Californians financially secure enough to own their homes is how the state’s inadequate and loophole-riddled bankruptcy protections too often make it impossible to hold onto that piece of the American Dream, just when it’s needed most. The problem lies with the law’s “homestead exemption,” a provision intended to shield a core amount of a bankrupt debtor’s home equity, when a court forces the sale of the house, in order to allow that debtor to land on their feet with a roof over their head and start afresh.

When Congress enacted the 1978 federal bankruptcy code, which is the basis for California’s and the other 49 states’ widely varying laws, the state’s homestead exemption was set at $40,000. Back in 1975,

» Read more about: Bankruptcy: Fixing California’s Homestead Exemption Law »

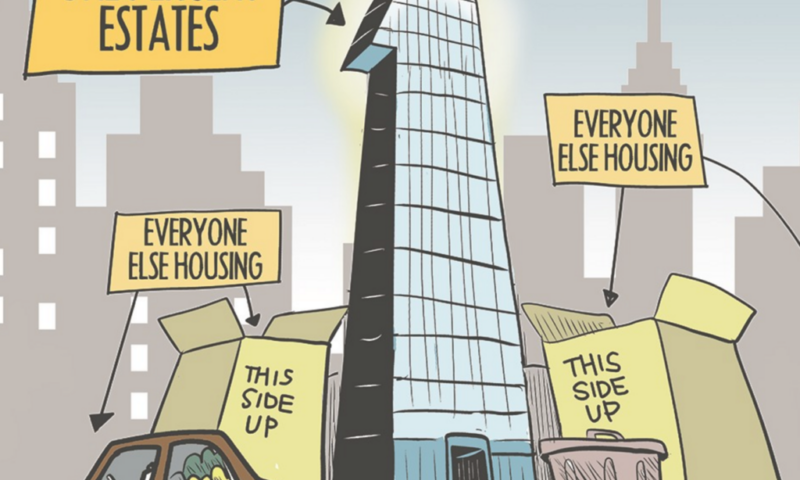

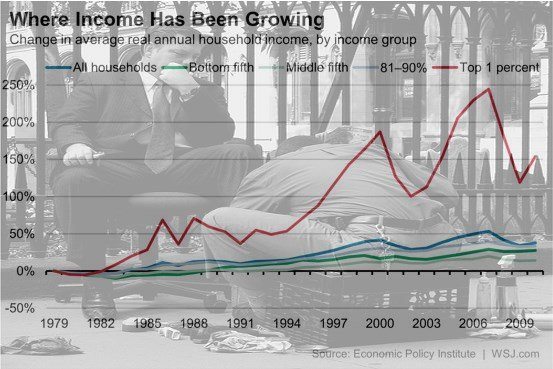

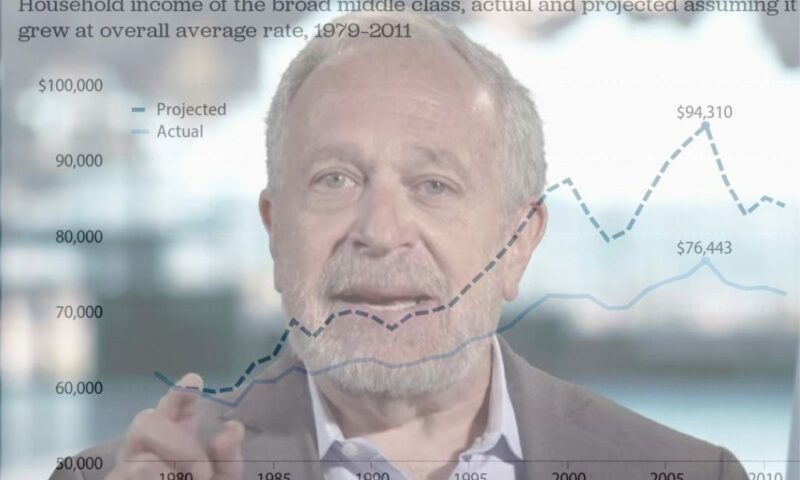

Americans don’t like inequality. We like to think of ourselves as a middle-class country where the top is not out of reach and the bottom doesn’t pose such a grim, cautionary specter that people fear for their livelihoods. We like to think that’s what makes us different from other societies. Or at least that’s the way it used to be.

CNN journalist John Blake, who grew up in Baltimore, remembers it this way: “Black men had good blue-collar jobs…Kids played baseball and basketball and every known sport at public fields and courts. We had summer jobs and internships.” Today, he says, “the factories and playing fields are locked behind gates or overgrown with weeds.”

Somehow the value of a stable, vital middle class has slipped from America’s vision for itself.

That shift characterizes America far beyond Baltimore.

As many as five million undocumented immigrants are waiting in limbo as the Supreme Court reviews challenges to President Obama’s 2014 executive actions, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Deferred Action for Parental Accountability (DAPA). But there’s one group that’s more than happy with the status quo.

A new look under the hood of the nation’s immigration detention system reveals a staggering trend: Immigrant detention has become increasingly reliant on facilities and services provided by private companies, which are driven by profit to keep or even expand existing services.

Companies like Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) and GEO Group — the nation’s two largest private prison companies — are benefiting from our bloated immigration detention system, which has grown by 75 percent over the last decade. Together, CCA and GEO Group operate eight of the 10 largest detention centers.

This year,

» Read more about: Immigrant Detention: Privatizing Misery »

For southwest Flint resident Qiana Dawson, it started when she was combing her 2-year-old daughter Rylan’s hair. Dawson was gently spraying water on the child’s head to ease the task, when Rylan started crying, as if she were in pain. She took her to a dermatologist.

And that was when her family discovered the problem with Flint’s water. “I don’t think you anticipate things like this,” Dawson said nearly two years later. “You take water for granted.” Even in hardscrabble Flint, drifting in and out of receivership since the last century, with a population that’s shrunk nearly 21 percent in 15 years and has one of the nation’s top crime rates — clean, healthy tap water seemed like a citizen’s basic right. Now Flint’s water is only safe for washing floors and flushing toilets. Dawson and her family of four have had to use bottled water for everything else—brushing teeth, cooking, washing vegetables,

» Read more about: Flint’s Water Disaster: A Lead-Pipe Cinch »

Reversing climate change and addressing income inequality are the twin challenges of our time. Solving them both means a safer, more stable future for generations to come.

If we don’t stop and reverse climate change, our environment and our economy could collapse. If we don’t address the growing gap between rich and poor, our political structures and our economy will continue to fray, robbing us of both the funds and the political will to address climate change.

These challenges are irreversibly linked — and we can’t solve one without solving them both.

That’s why progressives, labor leaders and everyone who cares about addressing these twin threats should oppose the California Public Utilities Commission’s recently proposed decision to require poor utility customers to subsidize richer customers and the new Wall Street-funded quasi-utilities serving these wealthy customers.

The CPUC’s decision is on a technical issue called Net Energy Metering: the system that provides subsidies for the installation of residential solar systems by forcing utilities to buy surplus energy generated on rooftops at an artificially high price.

» Read more about: Solar Decision Will Burn Low-Income Californians »

By now, many are familiar with the tragic details of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. But a key chapter in the story is being overlooked.

In February 2015, almost a full year before the news of widespread lead poisoning gained headlines, the world’s largest private water corporation, Veolia, deemed Flint’s water safe. It was hired by the city to assess water that many residents had been complaining about—a General Motors plant had even stopped using Flint’s water because it was rusting car parts.

Veolia, a French transnational corporation, declared Flint’s water to be “in compliance with State and Federal regulations.” While it recommended small changes to improve water color and quality, Veolia’s report didn’t mention lead.

Flint’s water system needs to be fixed today regardless of costs. But one thing should be completely off the table: privatization.

Often,

» Read more about: French Water Company’s Dirty Role in Flint »

For most people, the end of last year signaled a time for goodwill, reflection and family. But for many, the holiday season was marked by murder and mayhem, forensics and frustration. Released stealthily by Netflix, as if the doc series itself was a smoking gun planted for viewers to stumble across, Making a Murderer is a gift which when unwrapped is all at once fascinating, frightful and infuriating.

Making a Murderer follows in the vein of such true-crime masterworks as Joe Berlinger and Bruce Bruce Sinofsky’s groundbreaking 1996 doc, Paradise Lost, and 2004’s lesser known Death on the Staircase, as well as last year’s killer Serial podcast and the lauded HBO series The Jinx. Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi’s 10-hour opus retraces the twists and turns of a horrific series of events,

» Read more about: I Wake Up Streaming: Netflix’s ‘Making a Murderer’ »

Four years ago, Robin Kutchai lost her husband to cancer. “We got the diagnosis that his body was full of tumors two weeks before he died,” she said, perched at the bar of the Woodland Hills Hilton, where she’s temporarily holed up. They had been married 10 weeks after they’d met, 35 years ago. Telling the story, her large, neatly made-up eyes welled with tears.

After her husband’s death, Kutchai sold their Simi Valley house and bought a townhouse in Porter Ranch, where she found a sense of belonging to help her through her grief. “It was always such a wonderful area,” she said. “It was a place where I felt safe being alone.”

The AQMD insisted it lacked the authority to order the draining of the Aliso Canyon well.

That all changed dramatically this past autumn,

» Read more about: Porter Ranch: Nosebleeds and Dead Hummingbirds »

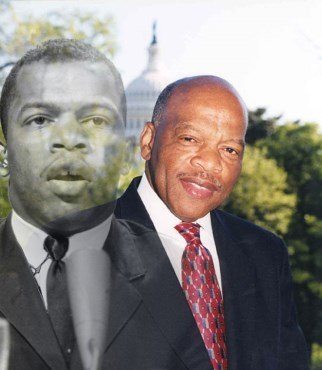

It was a long way from the elegant ballroom of downtown Los Angeles’ Bonaventure Hotel back to his Aunt Senovia’s tin-roofed shotgun shack in rural Alabama. But somehow Georgia Congressman John Lewis, the iconic civil rights leader whose life began in the segregated Jim Crow South, was able to pull it all together for one thousand-plus people at the Martin Luther King Jr. Labor Breakfast, hosted by the L.A. County Federation of Labor.

It was a long way from the elegant ballroom of downtown Los Angeles’ Bonaventure Hotel back to his Aunt Senovia’s tin-roofed shotgun shack in rural Alabama. But somehow Georgia Congressman John Lewis, the iconic civil rights leader whose life began in the segregated Jim Crow South, was able to pull it all together for one thousand-plus people at the Martin Luther King Jr. Labor Breakfast, hosted by the L.A. County Federation of Labor.

Speaking before a giant photo of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where he was beaten unconscious in the aborted 1965 Selma to Montgomery civil rights march, Lewis displayed the speaking and preaching skills he said he developed at age 14 from practicing in front of the chickens who were his responsibility on the family farm. “It seemed like more of those chickens listened to me then, than members of Congress do today,” he quipped.

Lewis’ father was a sharecropper and a cotton picker until 1944,

Flint was a failure of government — but it didn’t have to be so. And government wasn’t the root of the problem. It was about the people, and ideas they advocate, who have taken control of governments across the country.

Water is a public good provided by public institutions — i.e. governments. It should be clear now that “running government like a business” (the privatizers trope) means you don’t invest in places that don’t have markets that can afford to buy your products. It didn’t work for Flint and it doesn’t work for America. Government needs to be run like a government — clear about its mission, run by competent people (yes, bureaucrats) committed passionately to the public good.

The tragedy of Flint should never have happened, but at this point, the evidence is undeniable and the suffering is real. Fixing Flint is an urgent priority.

Robert Reich stepped down from his post as Labor Secretary in 1996 to spend more time with his teenage sons, Adam, now a sociology professor at Columbia University, and Sam, a writer and director who heads the video department at the popular comedy site CollegeHumor.com. (Reich and Clare Dalton divorced in 2012; he has since remarried.) Resuming the academic career he had embarked on in 1980 as a professor at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, he took a position at Brandeis University and published a well-received serio-comic memoir about his years in the Clinton administration, Locked in the Cabinet.

Other than an unsuccessful run for governor of Massachusetts in 2002, he has spent most of the past two decades as a de facto Economic Educator in Chief for millions of Americans. Reich, who co-founded the American Prospect magazine,

It’s two weeks before Thanksgiving, and a crowd of 500 people has filled the Silicon Valley Commonwealth Club to hear former U.S. Labor Secretary Robert Reich discuss a decidedly less than festive topic: How the economy is leaving most Americans behind. The subject, which inspired Reich’s latest book, Saving Capitalism, hits particularly close to home here, where uber-rich tech titans coexist with legions of low-wage workers, even as the middle class is increasingly squeezed out of nearby communities like Redwood City and Milpitas by ever-rising housing prices.

But Reich has no intention of bludgeoning his audience with bleak statistics and grim predictions. “As you can see, the economy has worn me down,” says the 4-foot-11-inch Reich, pausing as laughter spreads across the room. “Really, before the Great Recession I was, you know, 6 foot 2.”

Moments earlier,

Last Monday was an important day for America’s shrinking middle class. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, a case that could impose radical new limits on the rights of public-sector workers—like teachers, nurses and firefighters—to join together to win better lives for their families and communities.

Last Monday was an important day for America’s shrinking middle class. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, a case that could impose radical new limits on the rights of public-sector workers—like teachers, nurses and firefighters—to join together to win better lives for their families and communities.

What’s at stake is a basic democratic principle: All public workers that benefit from collective bargaining should be required to pay their fair share for those efforts.

So it’s no surprise that the Friedrichs lawsuit was filed by the Center for Individual Rights, a law firm with ties to anti-worker special interests—like the Koch brothers and ALEC.

These are the same interests that have spent decades campaigning to weaken the ability of working people to join together against corporate power and the interests of the One Percent.