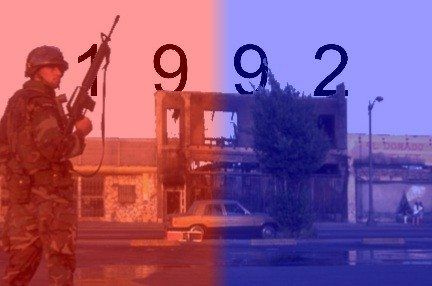

Ralphs had already left my neighborhood in Gardena — known as one of the most diverse cities in L.A. County — at the time of the ’92 riots. I remember the brightly lit grocery store with wide aisles being replaced by a Payless Foods with cramped aisles where food items like Sunny Delight and Cool-Ranch Doritos all of a sudden were double the price.

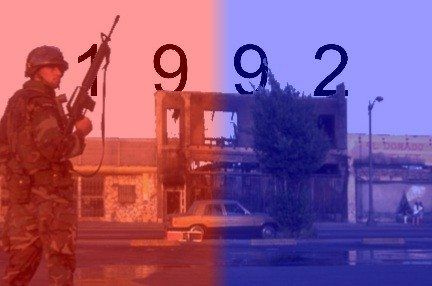

I remember a lot about ’92. I was 13 and lived in an apartment with my sister, mom and dad in the black part of Gardena, a trend we started where brown folks were creeping slowly into traditionally African-American neighborhoods.

It was the year before I entered high school. At the time, I attended Maria Regina Catholic School across the street from where I lived. Most of the students and my friends were African-American or Latino. I had to make a choice about which school to go to,

(Note: This post first appeared April 28 on L.A. Progressive.)

According to US Secretary of Labor Hilda Solis, more people die in the American workplace in a single year than have been lost in nine years of war in Iraq. “Each day in America, twelve people go to work and never go home,” she told the audience at the Action Summit for Worker Safety and Health held at East Los Angeles Community College on April 26, one of many events leading up to Workers Memorial Day, April 28, an annual date of remembrance for those killed, injured, or sickened on the job.

María Elena Durazo, Executive-Secretary-Treasurer of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, AFL-CIO, reported there were 500 work-related deaths in 2011 in California and “Workers are still being fired for speaking out in order to avoid death.”

This loss of life and countless serious injuries,

» Read more about: Killer Jobs: Policing America's Dangerous Workplaces »

By Shomari Davis

It’s no secret that the disappearance of manufacturing in Los Angeles and other urban centers over the past few decades has hit communities hard. When the factories closed, they took with them not only jobs, but the path to a better future for countless residents.

What you may not know is that, for the first time in a long time, we have a real shot at bringing an important manufacturer back to L.A. – and along with it jobs and hope.

The company is Siemens, one of the world’s largest railcar producers. Siemens is one of the finalists for a $1 billion railcar contract, which will be awarded by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). If chosen, the company will bring more than 1,100 jobs to the U.S., many of them right here in L.A.

Here’s the bad news: MTA staff has recommended that the board go with a bid from the Japanese firm Kinkysharyo.

» Read more about: MTA, Bring Manufacturing Jobs Back to LA! »

April 29, 1992. For me, at the time an 11-year-old Black child living in a low-income section of Long Beach, that date represents more than a civil disturbance. While too young to clearly understand concepts like oppression, I was old enough to know the profound frustration associated with being poor within an economy that continued to deny the aspirations and dreams of many in my neighborhood.

Those were the years immediately following Reaganomics and the George Bush “read my lips” tax plan. The good ol’ colored people in communities like South Los Angeles, Compton, Watts and Long Beach were supposed to wait quietly and patiently for the day when the free market, through the trickling down of quality jobs, health care and good schools, delivered the gift of liberation we had all hoped for. Unfortunately, with each passing moment, those promises faded deeper and deeper into a dark empty background – with no hope of ever resurfacing.

» Read more about: 1992 Remembered: Why Los Angeles Had to Burn »

This past Monday, I drove to Long Beach to participate in the Living Wage Campaign. A large group of us met up at the North Long Beach Christian Church at 2 p.m. I was nervous, the way I used to get on the first day of school. There were a bunch of kids I didn’t know and some of them were smoking in the parking lot — I was the new guy, unsure and walking around aimlessly.

The Long Beach Coalition for Good Jobs and a Healthy Community has been in a fight to get its hotel workers out of poverty wages. The organization is attempting to get an initiative on the November ballot that would require hotels with more than 100 rooms to pay their workers $13 an hour and give them five mandatory paid sick days per year.

Of course an initiative like this requires lots and lots of signatures from registered voters,

» Read more about: Left-Wing Nut Jobs – A Canvasser’s Tale »

Ruben Martinez is a professor of literature and writing at Loyola Marymount University; his most recent book, Desert America: Boom and Bust in the New Old West, will be released in August. At the time of 1992’s civil unrest, he was a reporter for the L.A. Weekly. Martinez spoke to Frying Pan News about his coverage during that volatile week.

Frying Pan News: What was your assignment that first day?

Ruben Martinez: I was at the courthouse in Simi Valley, camped out with Eric Spillman of KTLA – I couldn’t get inside, there were too many people there already. Outside, all the veteran journalists had their lawn chairs and umbrellas — they’d been there for weeks. The spectacle of it impressed me.

Did the acquittals shock the media?

Yes. A really motley crew of people – reporters,

» Read more about: 1992 Remembered: Prophets and Prisoners of War »

What do I most remember about the uprising of ’92? That certain feeling of powerlessness.

I have so many vivid memories: People swarming the supermarket on Third Street and Bonnie Brae, just west of downtown, rushing out with baskets loaded with diapers and food supplies. Outraged young men standing in the middle of Crenshaw Boulevard near Adams, blocking my way home — at least until I figured out how to go around them. Burning buildings all around where I worked in Pico Union, and where I lived in South Los Angeles. And then the drawings of my five-year-old twins, showing burning buildings and people running for their lives.

I was a 32-year-old mother of three young children, and working as the Executive Director of the Central American Refugee Center (CARECEN) in Pico Union. I was living in a four-bedroom bungalow house near Crenshaw and Venice boulevards,

» Read more about: 1992 Remembered: Smoke Gets in Your Eyes »

If you haven’t checked this out yet, you need to. Now.

According to the New York Times, Walmart fueled its rapid expansion in Mexico with millions in bribes paid to get building permits and land use approvals through quickly. The story is based on a whistleblower, who told Walmart leadership about the issue, which they confirmed was very likely true before allegedly sweeping the whole thing under a rug. The Washington Post reports that the Department of Justice is investigating.

From an L.A. perspective, the money quote is here: “In an interview with the Times, Mr. Cicero said Mr. Castro-Wright had encouraged the payments for a specific strategic purpose. The idea, he said, was to build hundreds of new stores so fast that competitors would not have time to react. Bribes, he explained, accelerated growth. They got zoning maps changed.

» Read more about: WebHot: Walmart Bribery Scandal Explodes »

(Editor’s Note: Frying Pan News continues its series about the 1992 unrest with this account told to us by Erin Aubry Kaplan.)

I was living in Inglewood in 1992. When the verdicts came in I was getting a facial — we were all really outraged in the salon. At that time I was teaching adult education courses — basic English and math for GED exams, plus ESL classes. I felt like I had to do something and a teacher friend and I heard there was a rally at the First AME Church. I was excited — I hadn’t really seen this kind of energizing in L.A. before. But as we drove to FAME people were filling up the streets and the energy felt dangerous.

We never made it: This guy threw a trash can into the street and someone tried to stop a motorist.

» Read more about: 1992 Remembered: From Inglewood to Brentwood »