As our nation pauses to observe Labor Day this week, you have to wonder what the future holds for American workers. Rising income inequality, a dwindling middle class, the growth of low-wage jobs without benefits, and unemployment rates that remain uncomfortably high should make us wonder whether we’ve allowed the American Dream to become a mythic fairy tale.

While these realities are certainly dire and downright depressing, they are not insurmountable.

Last month, President Obama began laying out a plan to rebuild America’s manufacturing base and shore up job security with good wages in stable industries. He called for rewarding companies for keeping jobs at home or bringing them back to the U.S. And, he said that we can and must train workers — especially those left farthest behind by the economic downturn — to get on new career tracks that lead them to the middle class.

» Read more about: Transit Investments Can Get Manufacturing Moving Again »

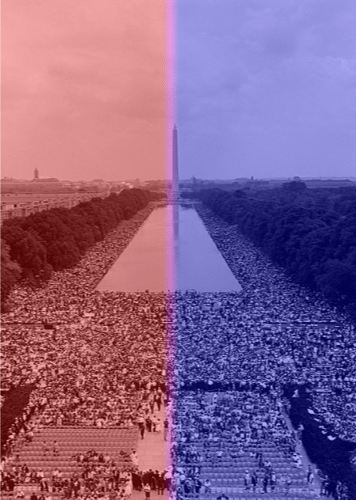

Of all the commemorations of the March on Washington, the one that will best capture its spirit isn’t really a commemoration at all. Thursday, one day after the 50th anniversary of the great march, fast-food and retail workers in as many as 35 cities will stage a one-day strike demanding higher wages.

Of all the commemorations of the March on Washington, the one that will best capture its spirit isn’t really a commemoration at all. Thursday, one day after the 50th anniversary of the great march, fast-food and retail workers in as many as 35 cities will stage a one-day strike demanding higher wages.

Sadly, the connection between the epochal demonstration of 1963 and a fast-food strike in 2013 couldn’t be more direct.

The march 50 years ago was, after all, a march “For Jobs and Freedom,” and its focus was every bit as economic as it was juridical and social. Even more directly, one of the demands highlighted by the march’s leaders and organizers was to raise the federal minimum wage — then $1.15 an hour — to $2. According to Sylvia Allegretto and Steven Pitts of the Economic Policy Institute,

With robots taking over factories and warehouses, toll collectors and cashiers increasingly being replaced by automation and even legal researchers being replaced by computers, the age-old question of whether technology is a threat to jobs is back with us big time. Technological change has been seen as a threat to jobs for centuries, but the history tells that while technology has destroyed some jobs, the overall impact has been to create new jobs, often in new industries. Will that be true after the information revolution as it was in the industrial revolution?

In an article in The New York Times, David Autor and David Dorn, who have just published research on this question, argue that the basic history remains the same: While many jobs are being disrupted, new jobs are being created and many jobs will not be replaceable by computers.

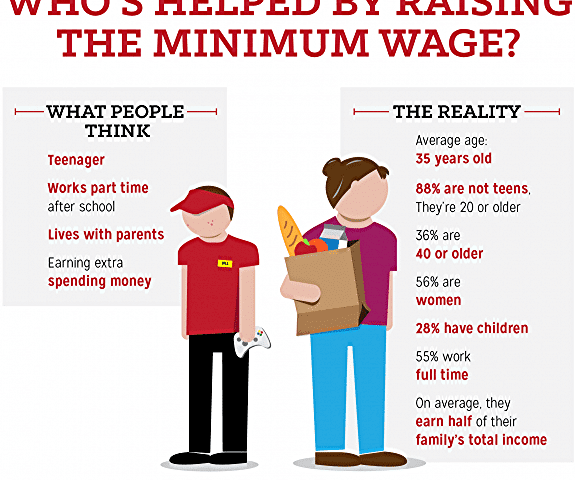

Infographic Source: Economic Policy Institute

(Today’s Los Angeles Times reported that strike actions against local fast-food outlets, launched by workers demanding a living wage, began early this morning. The following story from Equal Voice News sets the background for this day of national action.)

Fast food workers – who say their hourly wages are not enough to keep up with the cost of living – are planning a nationwide strike Thursday in about 35 cities. The industry employs about four million people.

Their message to restaurant chain owners and the public: Because of the pay, they often have to pit buying food against paying for their housing – and that, they say, seems strikingly odd in the United States.

In fact, some say they need food stamps to survive despite being employed.

A few days ago I had breakfast with a man who had been one of my mentors in college, who participated in the struggle for civil rights in the 1960s and has devoted much of the rest of his life in pursuit of equal opportunity for minorities, the poor, women, gays, immigrants — and also for average hard-working people who have been beaten down by the economy. Now in his mid-80s, he’s still active.

A few days ago I had breakfast with a man who had been one of my mentors in college, who participated in the struggle for civil rights in the 1960s and has devoted much of the rest of his life in pursuit of equal opportunity for minorities, the poor, women, gays, immigrants — and also for average hard-working people who have been beaten down by the economy. Now in his mid-80s, he’s still active.

I asked him if he thought America would ever achieve true equality of opportunity.

“Not without a fight,” he said. “Those who have wealth and power and privilege don’t want equal opportunity. It’s too threatening to them. They’ll pretend equal opportunity already exists, and that anyone who doesn’t make it in America must be lazy or stupid or otherwise undeserving.”

“You’ve been fighting for social justice for over half a century. Are you discouraged?”

“Not at all!” he said.

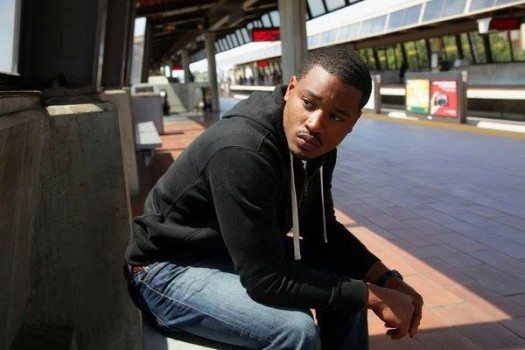

Fruitvale Station will not make many people’s lists as the feelgood film of the summer – it’s a semi-fictional account of the last day in the life of Oscar Grant, the troubled young black man who was mortally wounded by a transit police officer on an Oakland BART platform in 2009. Director Ryan Coogler’s debut movie opens with actual grainy cell phone footage, taken by bystanders, of the chaotic moments leading to Grant’s shooting after a melee had erupted on a train full of New Year’s Eve revelers.

Yet the story remains a powerfully optimistic work that shows Grant (Michael B. Jordan), in his last day alive, coming to terms with his criminal past as a small-time drug dealer. We watch as he tries to move his life in a new direction and become a better husband and father. And, despite Grant’s recurring moments of explosive personal confrontations, Coogler’s film knows when to pull back and take a restrained,

President Obama recently signed a bipartisan bill that ties student loan interest rates to the financial markets, which allows this year’s undergraduates to borrow at 3.9 percent interest — nearly half of what they would have paid if Congress had failed to act. As a recent college graduate, I, like many of my peers, was very excited to learn of this decision. However, while the federal government has done great work to help those students who are already enrolled in college, it is effectively failing those students who come from families at or below the poverty line.

President Obama recently signed a bipartisan bill that ties student loan interest rates to the financial markets, which allows this year’s undergraduates to borrow at 3.9 percent interest — nearly half of what they would have paid if Congress had failed to act. As a recent college graduate, I, like many of my peers, was very excited to learn of this decision. However, while the federal government has done great work to help those students who are already enrolled in college, it is effectively failing those students who come from families at or below the poverty line.

A recent Brookings Institute and Princeton University study notes that the federal government is spending around $1 billion per year on programs to help low-income students. Despite this funding, the four major college prep programs, Upward Bound, Upward Bound Math-Science, Student Support Services and Talent Search (known collectively as TRIO), have had “no major effects on college enrollment or completion.” The study shows that students from low-income backgrounds who earn college degrees are 80 percent less likely to be poor.

» Read more about: Paper Chases: College and Low-Income Students »

Fifty years ago, just a year out of high school, I sat in my parents’ small living room engrossed by images on the flickering black and white TV screen. Something called the March on Washington was running live — the whole event, as I recall, which network television did in those days. I’m not sure why I was not at work or why I was alone in the house, but I remember that tears came to my eyes, just as they do now as I think back on that day.

Fifty years ago, just a year out of high school, I sat in my parents’ small living room engrossed by images on the flickering black and white TV screen. Something called the March on Washington was running live — the whole event, as I recall, which network television did in those days. I’m not sure why I was not at work or why I was alone in the house, but I remember that tears came to my eyes, just as they do now as I think back on that day.

My parents were originally from the South, but both grew up in Southern California. My mother had been born in Mississippi, moved to Texas and then Inglewood. My father came from Texas to La Crescenta. After they married and my father became a minister, Northern California was home, but the ethos of white superiority and other ethnic and class inferiorities were engrained.

This week we mark the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Few would argue about the importance of Dr. King in U.S. history and the decisive role he played in the civil rights movement. Soon after his death, a campaign began to have King’s birthday declared a national holiday. Over six million signatures were collected on a petition to Congress to pass such a law, in what has been called “the largest petition in favor of an issue in U.S. history.”

Martin Luther King Jr. Day became a federal holiday in 1986.

Fourteen years later, MLK Day was observed in all 50 U.S. states for the first time.

And in 2006, Greenville County, South Carolina became the last county in the U.S. to officially make MLK Day a paid holiday.

Growing numbers of private employers also consider MLK Day a holiday.

» Read more about: L.A.’s Fox TV Strips MLK Day from Union Contract »

Union leaders and activists from around the country, in Los Angeles September 8 for the AFL-CIO Convention, will get a close look at a regional labor movement with membership numbers holding steady or even slightly increasing.

Union leaders and activists from around the country, in Los Angeles September 8 for the AFL-CIO Convention, will get a close look at a regional labor movement with membership numbers holding steady or even slightly increasing.

Compare this with much of the U.S., where the percentage of workers represented by unions is dropping rapidly and persistently.

L.A., more than most cities (and California, more than most states) has stayed a step ahead of an employer class determined to cleanse the global economy of collective worker power.

Credit Los Angeles and statewide unions for building tightly run coalitions with immigrant-rights and economic-justice groups; their brassy leadership and an electoral strategy which has – so far, at least – beaten back anti-union measures like Proposition 32.

AFL-CIO delegates from the de-industrialized Midwest, by contrast, have been facing relentless attacks from Republican governors and legislatures fronting right-to-work drives and laws restricting public employee bargaining rights.

» Read more about: AFL-CIO Convention Comes to Los Angeles »