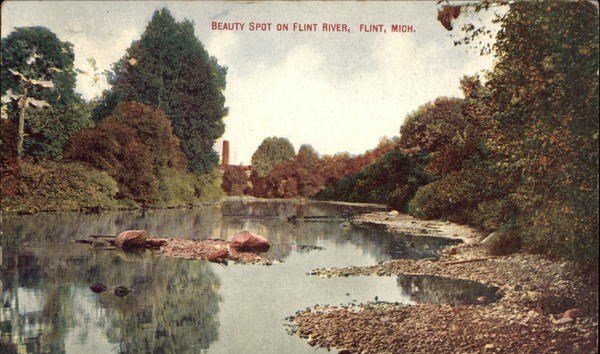

For southwest Flint resident Qiana Dawson, it started when she was combing her 2-year-old daughter Rylan’s hair. Dawson was gently spraying water on the child’s head to ease the task, when Rylan started crying, as if she were in pain. She took her to a dermatologist.

And that was when her family discovered the problem with Flint’s water. “I don’t think you anticipate things like this,” Dawson said nearly two years later. “You take water for granted.” Even in hardscrabble Flint, drifting in and out of receivership since the last century, with a population that’s shrunk nearly 21 percent in 15 years and has one of the nation’s top crime rates — clean, healthy tap water seemed like a citizen’s basic right. Now Flint’s water is only safe for washing floors and flushing toilets. Dawson and her family of four have had to use bottled water for everything else—brushing teeth, cooking, washing vegetables,

» Read more about: Flint’s Water Disaster: A Lead-Pipe Cinch »

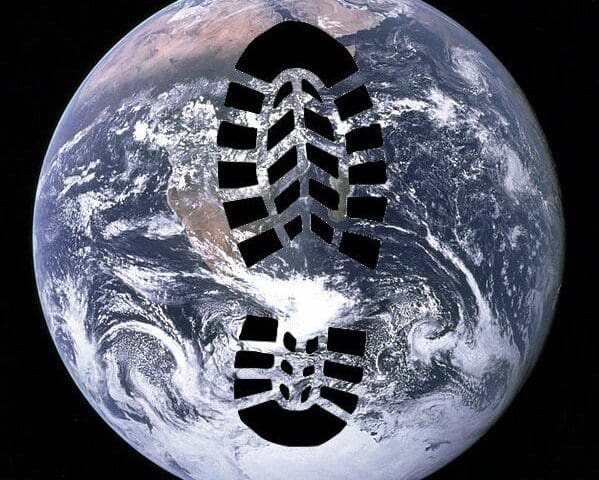

Reversing climate change and addressing income inequality are the twin challenges of our time. Solving them both means a safer, more stable future for generations to come.

If we don’t stop and reverse climate change, our environment and our economy could collapse. If we don’t address the growing gap between rich and poor, our political structures and our economy will continue to fray, robbing us of both the funds and the political will to address climate change.

These challenges are irreversibly linked — and we can’t solve one without solving them both.

That’s why progressives, labor leaders and everyone who cares about addressing these twin threats should oppose the California Public Utilities Commission’s recently proposed decision to require poor utility customers to subsidize richer customers and the new Wall Street-funded quasi-utilities serving these wealthy customers.

The CPUC’s decision is on a technical issue called Net Energy Metering: the system that provides subsidies for the installation of residential solar systems by forcing utilities to buy surplus energy generated on rooftops at an artificially high price.

» Read more about: Solar Decision Will Burn Low-Income Californians »

By now, many are familiar with the tragic details of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. But a key chapter in the story is being overlooked.

In February 2015, almost a full year before the news of widespread lead poisoning gained headlines, the world’s largest private water corporation, Veolia, deemed Flint’s water safe. It was hired by the city to assess water that many residents had been complaining about—a General Motors plant had even stopped using Flint’s water because it was rusting car parts.

Veolia, a French transnational corporation, declared Flint’s water to be “in compliance with State and Federal regulations.” While it recommended small changes to improve water color and quality, Veolia’s report didn’t mention lead.

Flint’s water system needs to be fixed today regardless of costs. But one thing should be completely off the table: privatization.

Often,

» Read more about: French Water Company’s Dirty Role in Flint »

Four years ago, Robin Kutchai lost her husband to cancer. “We got the diagnosis that his body was full of tumors two weeks before he died,” she said, perched at the bar of the Woodland Hills Hilton, where she’s temporarily holed up. They had been married 10 weeks after they’d met, 35 years ago. Telling the story, her large, neatly made-up eyes welled with tears.

After her husband’s death, Kutchai sold their Simi Valley house and bought a townhouse in Porter Ranch, where she found a sense of belonging to help her through her grief. “It was always such a wonderful area,” she said. “It was a place where I felt safe being alone.”

The AQMD insisted it lacked the authority to order the draining of the Aliso Canyon well.

That all changed dramatically this past autumn, when the air in the far northwestern San Fernando Valley community became saturated with the rotten-egg smell associated with natural gas — a consequence of a chemical added to the odorless gas to make it detectable.

» Read more about: Porter Ranch: Nosebleeds and Dead Hummingbirds »

Flint was a failure of government — but it didn’t have to be so. And government wasn’t the root of the problem. It was about the people, and ideas they advocate, who have taken control of governments across the country.

Water is a public good provided by public institutions — i.e. governments. It should be clear now that “running government like a business” (the privatizers trope) means you don’t invest in places that don’t have markets that can afford to buy your products. It didn’t work for Flint and it doesn’t work for America. Government needs to be run like a government — clear about its mission, run by competent people (yes, bureaucrats) committed passionately to the public good.

The tragedy of Flint should never have happened, but at this point, the evidence is undeniable and the suffering is real. Fixing Flint is an urgent priority. Fortunately,

Juan and Manuel Salvador Orozco Cadena, a pair of fishermen from Baja California, Mexico, pushed off from Punta Lobos on the morning of November 4, 2015. Earlier, the Orozcos had repaired the transmission of their outboard motor, but then it broke down again. As night closed in, the brothers floated helplessly in their open panga 30 miles off the Pacific Coast, making intermittent contact by cellphone, before being rescued by the Mexican coast guard.

At the same moment the Orozcos had first pushed off into the sea, Airbnb executives 1,200 miles away were celebrating the defeat of a San Francisco ballot initiative aimed at regulating the short-stay rental titan. What could possibly be the connection between two Mexican fishermen adrift in the ocean and a company valued by Wall Street estimates at $25.5 billion?

The answer is Chip Conley, a good-looking, 55 year-old fit guy with a shaved head and a charismatic smile whose official full-time job is Head of Global Hospitality for Airbnb.

» Read more about: Ambassador Recalled: Airbnb’s Chip Conley’s Mexican Misadventure »

Love. Joy. Peace. That’s the message of the season. From carols to holiday cards to street signs, even shopping mall windows. These words hover next to the pervasive images encouraging us to buy, but somehow they persist despite the maze of mercantile messages, because they are the deep longings of human beings.

“No justice, no peace!” is what workers and activists often chant on picket lines. It turns out that without climate justice, we will also have no world peace. A recent Los Angeles Times story on El Niño and its potential “long-distance” or “teleconnected” effects quoted researchers arguing that “it doubles the risk of war in much of the Third World.”

Our military accounts for 80 percent of all the fossil fuels consumed by the U.S. government.

Peace activists have long identified war and the preparations for it as a major source of human-caused climate change.

Seven years ago local officials in Marin County, California organized to form a nonprofit electricity company with the noblest intentions. Buying and selling electricity allowed the group, Marin Clean Energy (MCE), to route around the local utility giant, Pacific Gas & Electric, which for years had resisted its customers’ pleas for cleaner, more reliable power, all the while “greenwashing” its image with marketing campaigns. “People wanted more of a sense of how their dollars were being invested,” Alex DiGiorgio, MCE’s community development manager, tells Capital & Main. “They wanted more access to competitively priced renewable energy.”

They also wanted to “catalyze local project development,” DiGiorgio says, to see their electricity bills go toward something more beneficial for the local community than large hydroelectric dams, polluting gas-fired power plants and a nuclear facility built over an earthquake fault.

But critics of the local-power movement say agencies like MCE — whose very reason for being was to stimulate renewable energy development — mostly support already extant renewable facilities.

» Read more about: Power Struggle: Will Local-Energy Groups Come Clean? »

As Governor Jerry Brown touted California’s environmental initiatives and prodded world leaders in Paris to embrace tougher environmental policies during the United Nations summit on climate change, it was instructive to look back at how one of Brown’s top environmental priorities suffered a major defeat in the California Legislature this year.

That priority was to establish a 50 percent reduction in petroleum usage in cars and trucks by 2030. Brown’s failure to win its passage in an overwhelmingly Democratic Legislature clearly illustrates not only the influence of the fossil fuel lobby, but also the continued rise of a new breed of Democrats who are exceedingly attentive to big business, while tone-deaf toward their party’s traditional progressive base.

Petroleum reduction was a key part of a proposed law, introduced as Senate Bill 350, which also called for steps to increase energy efficiency in existing buildings and require that 50 percent of California’s energy come from renewable sources,

» Read more about: How Big Oil Spiked Jerry Brown's Climate Change Agenda »

You have to hand it to libertarian writer John Tierney. He doesn’t give up easily. His long-winded 1996 article, “Recycling Is Garbage,” allegedly smashed the New York Times Magazine‘s hate-mail record. It covered the same ground as his recent New York Times op-ed, “The Reign of Recycling,” stating: “Recycling may be the most wasteful activity in modern America: a waste of time and money, a waste of human and natural resources.”

Is recycling really “the most wasteful activity in modern America?” That’s quite a charge. (What about all that Kardashian coverage?) But it may be true that it would be cheaper to put all our waste in a hole someplace and forget about it. Assuming, as Tierney does, that there are enough conveniently located holes. It would be even cheaper to use the medieval method of tossing it in the street.

» Read more about: NY Times Writer Recycles Old Ideas About Waste and Landfills »

The debate may be over in the scientific community about the threat of man-made climate change. But as world leaders continue negotiating in Paris this week at an international climate conference, many questions remain about what it will take to come up with a workable plan to limit greenhouse gas emissions enough to avoid catastrophic warming.

University of Massachusetts at Amherst economist Robert Pollin injects a note of optimism into the discussion with his recently published book, Greening the Global Economy (MIT Press). Pollin estimates that we need to invest about 1.5 percent of global GDP annually in clean energy and energy efficiency in order to slow warming enough to maintain a livable planet. The good news, he argues, is that we can decarbonize our economy without sacrificing economic growth and prosperity. Capital & Main interviewed Pollin while he was in New York on a book tour.[divider]

Capital &

» Read more about: Robert Pollin Sees a Bit of Rainbow During Paris Climate Talks »

The story of Mary and Joseph leaving their small town for Bethlehem has spawned dramatizations, poems, carols and a lot more since it was first told in the late First Century CE. The Latin American enactment, called Las Posadas, runs for nine nights, from December 16 through Christmas Eve. Each night families make a procession through their communities, walking from one house to another, begging for space for the holy couple and a birthing place for the baby Jesus. At every home they are turned away – until one family welcomes these poor wayfarers, usually with warm drinks and sweets.

The festival reenacts the ancient commandment from the Jewish tradition that we should welcome the stranger, the foreigner, the immigrant – because at one time we were all newcomers to this land.

Most Americans have forgotten this and have instead become very fearful after the November Paris attacks. Even while 9,000 refugees from Syria,

» Read more about: Immigration Crisis: The Strangers Are Us »

On Thursday afternoon a fired-up, thousand-strong gathering of nurses and environmental activists packed into Los Angeles’ Pershing Square to voice their concerns about the bleak prospects of climate change, and to demand a global agreement that reduces greenhouse gas pollution. The rally was timed to coincide with the current United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris and other environmental justice protests taking place across the U.S.

Dubbed “The Climate Crisis Is a Public Health Crisis,” the event was organized by the National Nurses United (NNU), a labor union whose members were wrapping up a two-day convention at the downtown JW Marriott.

Rolanda Watson-Clark made the trip from Chicago, and told Capital & Main, “Nurses have always been at the front of social movements, so here we are.” She explained how, in the Windy City, inner city children are deeply affected by petroleum waste products in the air.

» Read more about: Nurses Address Climate Change: "Our Planet Is My Patient!" »

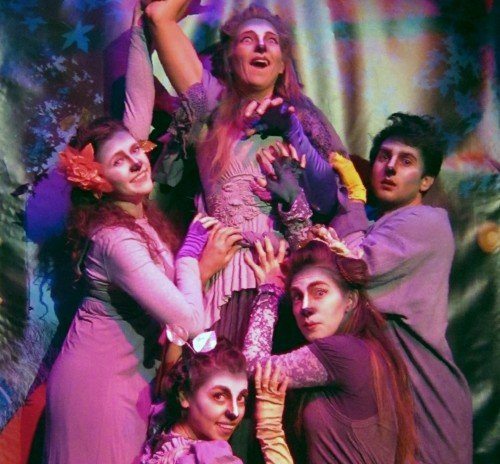

Today kicks off the start of VisionLA ’15, a Los Angeles arts festival performed to coincide with the United Nations’ Conference on Climate Change (COP 21) as it unfolds in Paris. Below are program notes from VisionLA ’15 – please refer to the group’s site for a complete schedule and more information.

Read Judith Lewis Mernit’s Interviews With VisionLA’s Organizers

[divider]

November 30 @ 6 p.m. – 10 p.m.

VisionLA Home Gallery – Bergamot Station,

2525 Michigan Ave., Building G1

Santa Monica

Join us for a celebration of the Power of Art to Make Change at our Gala Opening party for the VisionLA ’15 Climate Action Arts Festival. This opening event will launch L.A.’s first citywide climate action arts festival and is also the opening gala for our wonderful ART MAKES CHANGE fine art exhibition,

» Read more about: VisionLA Climate Change Arts Festival: November 30 Events »

Bad enough that the climate is changing and humans are causing it; worse, most of us don’t even want to talk about it.

“Where are the books? The poems? The plays? The goddamn operas?” asked author and climate activist Bill McKibben a decade ago on Grist, comparing the climate crisis to the AIDS epidemic, which, McKibben noted, produced “a staggering outpouring of art that, in turn, has had real political effect.”

To be fair, that has started to change: Authors such as Paolo Bacigalupi (The Water Knife) and filmmaker Larry Fessenden (The Last Winter) have begun to address environmental catastrophe in their works. But it’s likely that other authors, artists and goddamn opera writers have assumed that their climate-focused work would struggle for an audience: A recent Pew Research Center poll found that only 42 percent of U.S. citizens consider rising seas and global temperatures disturbing.

» Read more about: The Heat’s On: An L.A. Arts Festival Tackles Climate Change »

Will the United Nations conference on human-caused climate change move toward saving the earth for habitation? That’s what’s at stake as the heads of the world’s nations gather in Paris on November 30 through December 11. They intend to put teeth into the U.N.’s “framework” that is aimed to reduce carbon emissions, and which has been adopted by some 195 countries. But will they?

Bill Gates doesn’t think so. In an interview in The Atlantic, Gates praised countries for pledging to roll back emissions by 80 per cent, but cast doubts about their ability to reach that goal. It’s not that he thinks government is particularly inept and that the private sector could do it. He really doesn’t think that either can or will.

He believes that people will cut the easy stuff first, leaving the hard-to-do for the latter half of the time frame.

» Read more about: Paris Climate Change Conference: A Planet in the Balance »

Paul Duncan, a battalion chief with California’s state firefighting agency, was at home in Northern California enjoying a day off on September 12 when he got the message: A wildfire was burning on Cobb Mountain, about a dozen miles away from Hidden Valley Lake, where he lived with his wife and two daughters.

Duncan, 46, decided to leave and help knock down the blaze because he knew the fire unit in the area was already short-staffed from putting out on another conflagration. Besides, his nearly 30 years of experience persuaded him there was no way a fire burning on a mountain to the west could burn down to the valley floor and then race eastward to threaten the Duncans’ home.

His optimism was short lived. Upon arriving on Cobb Mountain Duncan got some troubling news. The fire he was fighting was heading toward his family.

» Read more about: Paradise Burned: How Climate Change Is Scorching California »

Old people often shake their heads and mutter about “the younger generation.” Or they’ll say to one another, “It’s not the way it used to be,” with a solemn look of dismay as if the world was “going to hell in a hand basket.” That’s the problem when an elder like me writes about human-caused climate change: I come close to being a cliché.

Perhaps such sentiments come from nostalgia for a time earlier in one’s life, an era viewed as simpler, slower and more familiar. Friends occasionally email me photo collections that supposedly represent a decade such as the 1950s without a single photo of anyone of color. It’s as if no one other than white people lived in this country. On the other hand, since most filmgoers are younger than my cohort, and if the top 10 grossing movies of a typical week are any indication, most people attending movies today choose deeply dystopian films about the violent end of civilization as we know it.

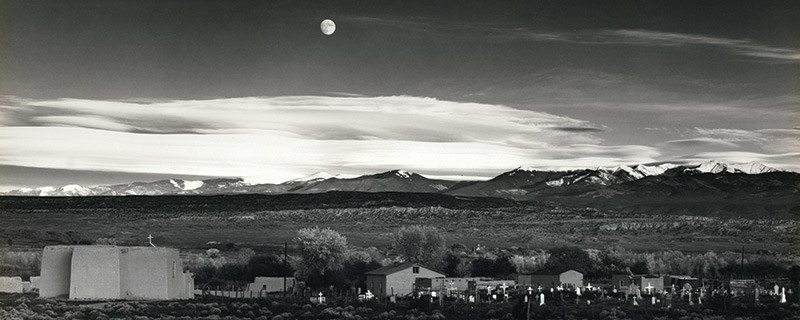

The rural Southwest feels vast and empty. Driving from Los Angeles to New Mexico, my wife Susan and I saw sweeping landscapes of alluvial fans and sheer cliffs, and mesas that stretched as far as we could see. Just the idea that people carved out a way of life on these lands left us in awe of our ancestors and, before them — centuries before them, millennia even — the first people who lived here.

People still live on this arid earthscape. They populate the small towns along the railroad tracks. They dwell in pueblos at the tops of mesas. They survive tucked into corners of cliff sides and in the bottomlands of rivers. Driving through such rugged beauty made us aware of the power of nature and the relative powerlessness of human beings in that kind of environment.

“Wild” no longer exists, even in the vast expanses of the Southwest. » Read more about: A Cease-Fire With Nature? »

Five trillion tons.

That’s how much ice melted in Greenland and Antarctica between 2002 and 2014 – and the reason why the seas already rise above low-lying islands in the South Pacific, displacing tens of thousands of people and threatening coral reefs that nurture uncountable numbers of sea creatures. Because of the climate change crisis we’ve become used to reading this kind of metric, along with the science-class comparisons that make it easy to visualize the colossal numbers involved. (Those five trillion tons, we are told, could make an ice cube 11 miles long on each side.) What we don’t always grasp, however, is the domino effect that one environmental disaster can have on the other side of the world.

A few years back, my wife Susan and I camped at Malakoff Diggins State Park, just north of Nevada City in Northern California. The place is famous for its earth formations that are similar to those of Brice Canyon National Park,